The heart of the Sundance Film Festival is Main Street in Park City, Utah. It starts out as a packed street full of festival-goers and eventually tapers off into a relatively busy arrangement of pedestrians and shop windows.

It is on Main St. where boutiques and art galleries are temporarily converted into physical existences of Kickstarter, AirBnB, CNN Films, Canon Lounge and so forth. Next to the internet commerce taking space are various attractions specifically made for Sundance. The busiest this year is the “Next Frontier: Claim Jumper”, a 3-story building dedicated only to Virtual Reality. Here is where people stand in line for 1 hour or sign onto digital wait lines that can last 4 hours – so high is the popularity of the 35 attractions powered by the Samsung Gear VR (the “Oculus Light”), HTC Vive and other VR systems.

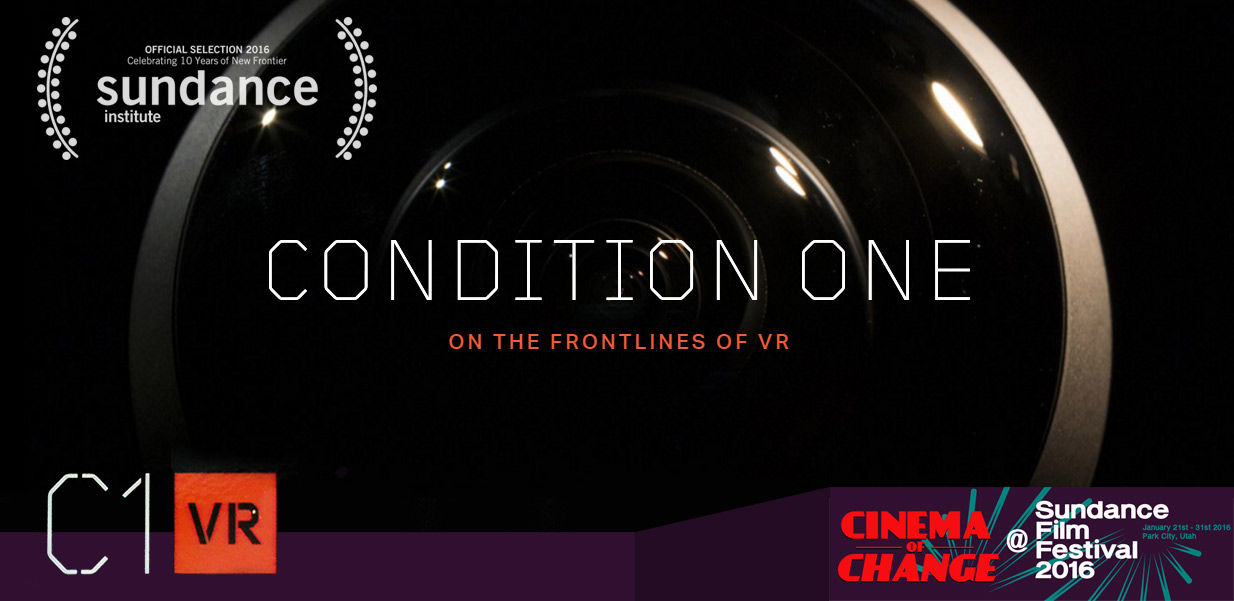

Across the street from this virtual amusement park is a quiet storefront that reads “C1 VR”. It took me 5 days to notice it, and I finally checked it out together with some Berkeley journalist friends. C1 is the abbreviation for Condition One, a startup based in Park City itself, which “creates “How big of an experience do you want?”, asks the lady in front. “I want the most intense thing you have”, spills the stimulus-addicted millennial in me.

“Then we’ll have you try our Factory Farm experience from Animal Equality.”

Nothing could have prepared me for what was to come.

Not Just Watching, But Being Present

An audience being fully immersed in their VR experience. The theater-like setting is not optimal, as the viewer is unable to take advantage of all 360 degrees of viewing. At Condition One, swivel chairs and plenty of leg space allowed for full spatial immersion in the VRIDE.

One of the main concerns in the quickly growing field of Virtual Reality is the concept of Presence. It is the requirement of VR immersion, namely the belief that one is actually present in the space that one is experiencing. any glitch, wrong refesh rate etc. takes you out of the suspension of disbelief and hence interrupts (tele-)presence.

How can we feel present in a space that literally only exists on a smartphone strapped to our head, with some lenses in front of our eyes and headphones on our ears? It’s not a fully resolved question, but we essentially fool our visual system into believing that what we see is completely real. Each eye usually gets a different image, creating stereoscopic imagery and a make-belive 3D effect just like you’d have it in a movie theater wearing 3D glasses. At the same time, there is no fixed screen any more; instead, the screen travels with your head and you experience it through circular goggles, which you soon forget about.

One of the most nifty components of our visual perception processing is our Vestibular System, where our body can sense acceleration and orientation. Imagine an accelerometer and a gyroscope, similar to the components of your smartphone, just built into our head right where our ears sit. Accelerating liquids in a 3-dimensional loop system tell our brain where we are currently looking and how strong the acceleration is. If there is an offset between the inputs of the Vestibular system and the inputs from our eyes, we become dizzy and call it motion sickness. Car sickness, sea sickness, simulator sickness – they’re all from the same family. Some of us have thrown up because of motion sickness, others just feel miserable. The evolutionary use? It’s one of the ways the body detects poisoning: If one sense delivers false or delayed information, it might be that the body has ingested a toxic substance and needs to expel it. Now that we have developed systems such as boats, cars and airplanes, our evolutionary biology is in slight disagreement with our technological evolution.

This is no different in VR, and any delays in the visual information can cause simulator sickness. But when everything is in perfect harmony and synchronization, when we have around 95 frames per second, the world inside the stereoscopic VR headset becomes a reality – and we become present in it.

What makes VR unique now is that – usually – you have 360 degrees of movement freedom into any direction. When you look down, the image in front of your eyes seems so real yet your body is not present, that is a strange experience. It’s the experience of presence – the belief that the virtual reality around you has become real. With (usually dynamically generated as per orientation and motion) binaural audio fed through headphones (which provides us with stereophonic sound), the sense of reality becomes even stronger. This class of dynamically simulated sound delivered as stereo binaural audio is referred to as 3D Audio, and synchronizes perfectly with our head motions. It allows us to not only watch something, but actually exist within that space, as an invisible observer. What becomes apparent in this deduction is the great applicability of live action Virtual Reality experiences as an Immersively Documented Experience. I propose to abbreviate and classify these experiences as VRIDE (Virtual Reality Immersively Documented Experience).

Take Me on a VRIDE

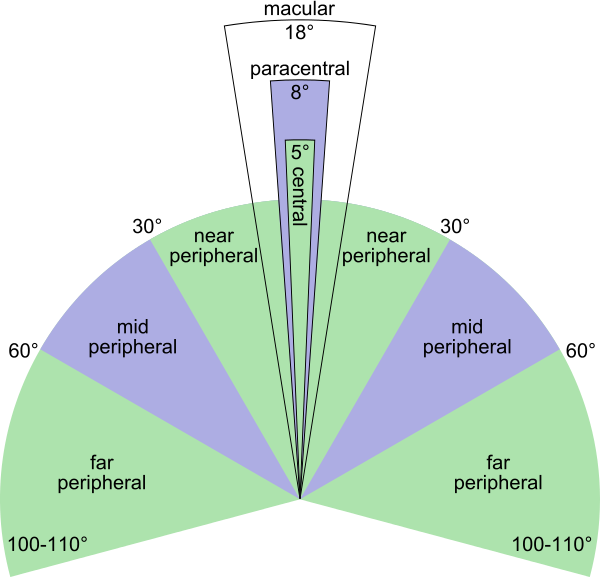

Once we wear a simple VR set such as the Gear VR (the device Condition One uses to present its VRIDEs), the documentary filmmaker can take us anywhere in the world. It is a bit like watching the good old IMAX nature films that took us into the depths of the ocean, onto exotic islands or into outer space. While in the old IMAX experience, you had a vertical and horizontal (nearly square format) field of view of 90-150 Degrees. The sheer size of the IMAX screen allowed a viewer to feel fully immersed if they ignored their peripheral vision and didn’t move their head. These IMAX experiences were powerful – you’d see animals larger than life, and often feel close to nature despite sitting in a dark theater in an urban center.

Now, with VR, the full immersion into nature and environment can take place just about anywhere. Noise-cancelling headphones are obviously a requirement if the viewer is in a noisy environment, but other than that, the real world disappears once one goes on a VRIDE. In this experience, the passive viewer turns into an active observer – one is able to turn their head and observe the world in the most familiar of ways. In the case of Condition One, I was taken into an industrial pig farm and later a slaughterhouse. What becomes uniquely powerful in this scenario that differentiates a VRIDE from a, say IMAX experience or Facebook PSA video on animal cruelty, is the positional relationship between viewer and mediated subject.

Let’s imagine four scenarios: We see a pig being slaughtered in real life, we watch a pig being slaughtered on IMAX, we watch the killing in a Facebook video, or we experience the slaughter in a VRIDE.

- Real life observation: We will respectfully keep a distance to the pig, turn our head and cover our ears if it is too much, but have strong social pressure to not leave the room. All sensory organs transmit information to our brain that is consistent with “pig slaughter”, including taste and smell. When we look down or at our hands, the body is present. Most likely, we will be looking down at the pig, as it is much shorter than us.

-

IMAX experience: The screen is so big that even when we look away, we probably catch a glimpse of what is happening. The dark theater nearly disappears in our vision, so the viewer and the large screen are quite alone with each other. We can cover our ears if the sound is too much. Taste and smell are not affected at all. Most likely we will be looking down at the pig, as the IMAX cameras are large and need proper space on a tripod to be recording.

- Facebook video: The viewer sees their own hands, keyboard, a screen, a facebook interface, and finally, the video – all at once. Despite our central vision being mostly on the video, we still notice the whole world around us – wether that is a messy desk, a cafe or our hands holding the smartphone the video is playing on. Sound might or might not even be turned on. We can pause, scroll away or click away any second; it’s trained behavior. Most likely we will be looking down at the pig, as the video might have been recorded as a hidden camera on someone’s suit button, or as a Handycam video at shoulder level.

- VRIDE experience: Our body disappears completely, as does our environment that we are currently sitting or standing in. We can see 360 degrees around us, top and bottom. The camera rig is very small, so there’s a good chance that we are in the cage together with the pig, or right next to it on the floor as it is spasming and bleeding to death; the pool of blood forming around us. The sound is fully immersive, and our only option to end the experience or avoid the sound completely is to rip the entire gear off our head. The other option for avoidance we have is to turn away and stare at the ceiling or another part of the factory – but we’ll hear the squealing regardless. Smell, taste and touch stay unaffected.

It becomes very clear that the VRIDE is closest to real life, and while having a multitude of missing senses, the audiovisual experience in a VRIDE can be even more intensive than in real life. This is due to the ability of the filmmaker to choose perspective for us and i.e. place us inside the cage together with the pig – a place we would otherwise not have, were we just visiting the pig factory. Also, watching a pig from below rather than from above changes a lot about how we see the pig – inferior or superior to us, physically speaking. Watching it from below or its eye level places us in a position of equality and respect.

The VRIDE Empathy Machine

This change in perception is the reason why people call VR the new “Empathy Machine”. We as an audience are immersed in the life and environment of other humans, animals or plants. We’re body-less, seemingly invisible points of consciousness that can only observe and experience. It’s a strange feeling, but once the concept of Self disappears, so does one’s ignorance of the world around us. Since we ourselves no longer exist, that which is around us gets all of our emotional attention. VR turns us from a rather selfish main character in our own lives to an empathic observer in the lives of others.

A man experiencing Animal Equality’s VRIDE “Factory Farm” at Condition One. Note that he is standing, allowing for full 360 degrees of movement freedom.

What I experienced at the Condition One exhibition was clearly a whole new level of audience involvement in subject matter. I don’t see so much of a future in staged, fictional live action VR entertainment, but the documentarian end of things – transporting an audience into a real environment and letting them experience this world up close – is an incredibly powerful opportunity for filmmakers.

EDIT: Animal Equality has uploaded a trailer for the experience, as well as the Factory Farm experience itself. Please note that you ABSOLUTELY should watch it on a VR Headset, as the “real deal” experience is 5-10 times stronger than just using your cursor on a 2-D youtube interface.