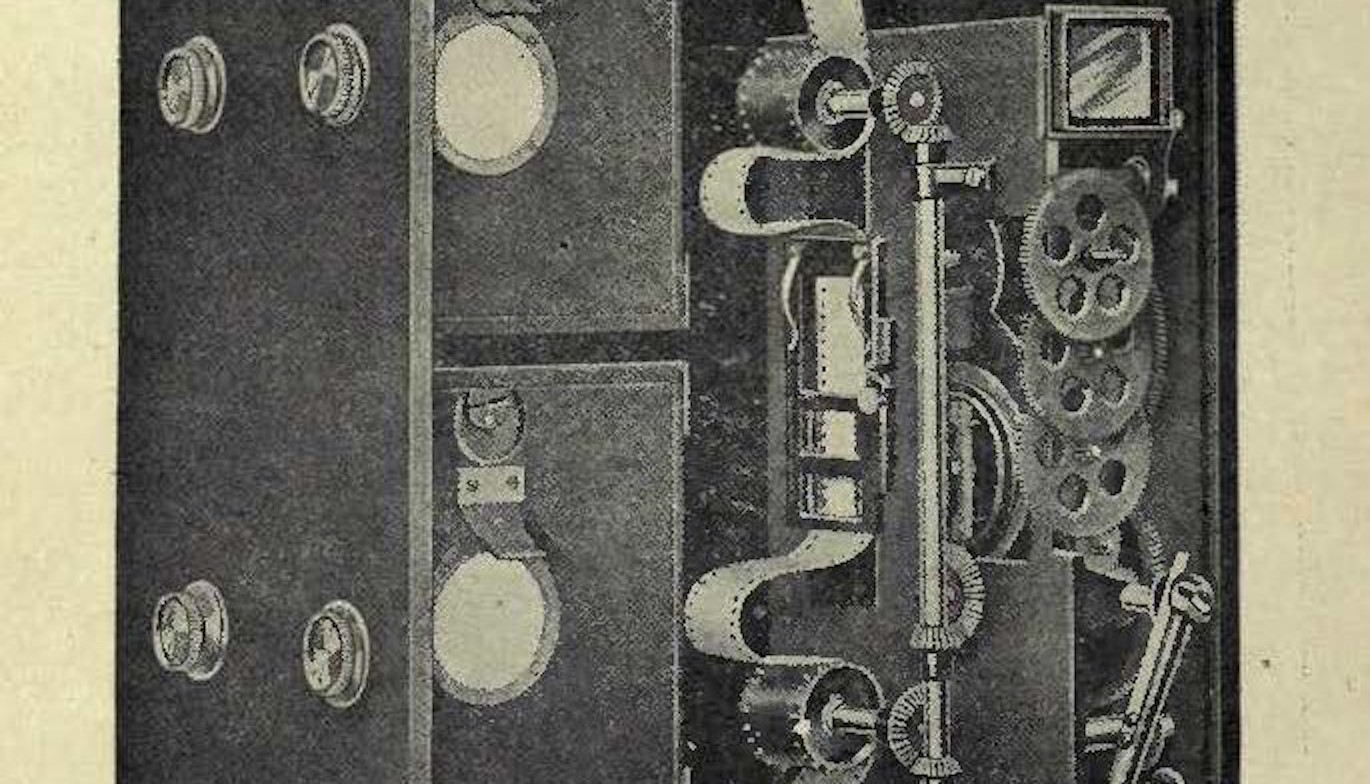

In 1916, Henry D. Hubbard, the Secretary of the U.S. National Bureau of Standards, spoke to the inaugural meeting of the Society of Motion aturengineers (SMPE), a group soon to be at the forefront of standardizing filmmaking technique and technology. Hubbard spoke with eloquence on what he dreamt the art form could become and its potential impact on the world:

To me the motion picture is the wonder of the world in its effects and possibilities. Its uses in education, science, recreation, industry, engineering, and social movements make it vie in interest and power with the printing press itself. (n. pg.)

For Hubbard, filmmaking was nothing less than the new printing press. While certainly there was some physical similarity, he spoke to loftier reasons for his comparison:

[Filmmaking] speaks the universal language of action. It is the magic carpet of Bagdad to take us to all lands, under sea and under land, among the clouds, to fairyland, and into the world’s markets, laboratories, hospitals, and factories. In portraying the flight of a bullet it magnifies time, in recording the unfolding of a flower from the bud it compresses days into seconds…. The quickening effect of this wonderful art upon social evolution is beyond estimate. To say that as an art it is in its infancy is to state the obvious. Its possibilities are limited only by the power of the creative imagination and the technical powers of the engineer. (n.pg.)

For Hubbard, filmmaking possesses inherently limitless ability and authority that exceeds that of the printing press. Movies speak a “universal language,” something the printing press, often bound by a specific language, cannot. Of course, Hubbard spoke of the silent film of the era, a largely visual and musical medium. Written and spoken language was then generally restricted to title cards and text in the shot (for example, a newspaper headline). For Hubbard, the lack of a specific language proved critical to filmmaking’s appeal and power.

Leading film pioneer C. Francis Jenkins echoed this belief at a 1917 SMPE conference, but he expanded on Hubbard’s reasoning:

The invention of the printing press, in the 15th century, gave a tremendous impetus to learning, but it appealed only to a class, for it was limited to those who could read. The invention of the motion picture of the 20th century began a second and greater era of learning for it speaks to the masses as well; to the old and young to the illiterate as well as the learned of every tongue, and it should not be forgotten that the illiterate of our earth constitute a body many times greater than those who can read. Again, the printing press must print for each man in his own tongue, while the motion picture prints in a language all can read. The printing press is autocratic, the motion picture democratic. (Jenkins n. pg)

To Jenkins, the motion picture became a force for democratization for the world, allowing all to share in its wonder and power — “the old and young to the illiterate as well as the learned of every tongue.” Jenkins referred to filmmaking the “picture press,” a striking name for this then new art form.

The subsequent introduction of the spoken word in the late 1920s limited what Jenkins and Hubbard specifically praised about the art as language and its myriad of forms entered the medium. By gaining specific voice, filmmaking lost its universality as the “picture press.”

Works Cited

Hubbard, Henry. “Standardization.” Society of Motion Picture Engineers – Incorporation and By-laws. July 24, 1916. Washington, D.C. New York, N.Y.: The Society of Motion Picture Engineers , 1916.

Jenkins, C. Francis. “The Motion Picture Booth.” Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. October 8-9, 1917. New York, NY. New York, N.Y.: The Society of Motion Picture Engineers, 1917.