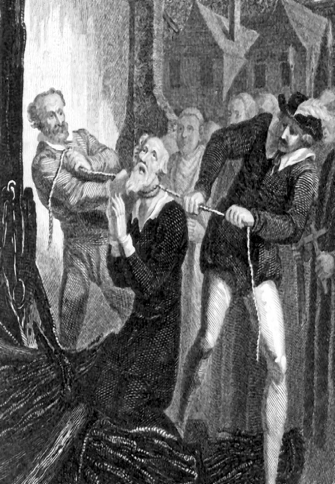

Translating culture is a pursuit that carries with it a terrifying history—on October 6th of 1536, in the town of Vilvoorde, just north of Brussels, British scholar, William Tyndale was betrayed, imprisoned, suffocated, and burned at the stake. The crime that led to his brutal execution? Translating the Bible from Greek to English, and in doing so, delivering a counter punch to Pope Paul III’s Catholic foothold on Europe. Tyndale was not alone in his rebellion or punishment. Almost two hundred years before him, the Czech theologian and Roman-Catholic priest, Jan Hus committed himself to a new interpretation of Biblical philosophy that led to a Bohemian reformation and staggered denominations upon Christianity in addition to sparking accusations of heresy that no doubt assured his execution. In fact, these apocryphal instances of brutality in the vain of God could inspire their own horror film franchise, and almost 500 years later Hollywood carries on the tradition of marrying fear and translation.

Translating culture is a pursuit that carries with it a terrifying history—on October 6th of 1536, in the town of Vilvoorde, just north of Brussels, British scholar, William Tyndale was betrayed, imprisoned, suffocated, and burned at the stake. The crime that led to his brutal execution? Translating the Bible from Greek to English, and in doing so, delivering a counter punch to Pope Paul III’s Catholic foothold on Europe. Tyndale was not alone in his rebellion or punishment. Almost two hundred years before him, the Czech theologian and Roman-Catholic priest, Jan Hus committed himself to a new interpretation of Biblical philosophy that led to a Bohemian reformation and staggered denominations upon Christianity in addition to sparking accusations of heresy that no doubt assured his execution. In fact, these apocryphal instances of brutality in the vain of God could inspire their own horror film franchise, and almost 500 years later Hollywood carries on the tradition of marrying fear and translation.

Since the first decade of the 21st century, American cinema has made concerted efforts to gobble up international features and existing properties, but how does its translation of international horror coordinate Hollywood on the X-Y axis between culture and industry? And what does the onscreen representation of women in the nightmare world tell us about our female gaze?

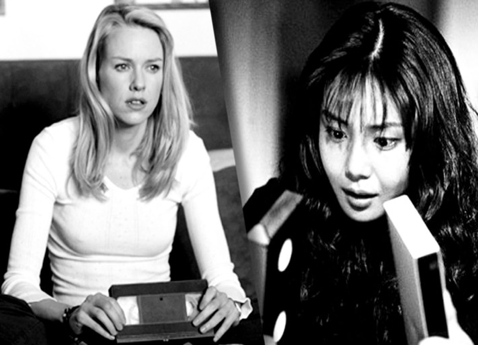

Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002) is a Hollywood stab at Hideo Nakata’s Japanese horror mystery, Ringu (1998). Originally adapted from Koji Suzuki’s novel, the movie is a freaky fable that follows an investigative reporter and her ex-husband as they track the haunted bread crumbs of an enigmatic video tape that curses its viewers. After watching the tape, audiences are doomed to die in a seven days. High concept, no doubt, but both the American and Japanese versions have found not only critical satisfaction but a financial success that continues to balloon; the American re-make established an audience and inspired two sequels, the most recent being the not-so-cleverly titled Rings in 2017.

In his Forbes review of the movie box office for the weekend after Rings’s release, Scott Mendelson reminds us that “Gore Verbinski’s The Ring was an absolute horror sensation in 2002 ($129 million from a $15m debut weekend and $248m worldwide on a $48m budget).” But The Ring‘s financial success was just the slope of the iceberg, considering American audiences received the film so well that the film is credited for kick-starting a renaissance of horror features, re-makes, and franchised screams that, like the British Invasion of mid-sixties rock ‘n’ roll, reinvigorated its genre.

Ringu floats along with a pace that is more reminiscent of a foggy noir nightmare, where the Hollywood version streamlines the horror and takes quicker breaths. Verbinski concerns himself less with mood than with special effects that liken a haunted house shock-and-awe experience. Certainly pace can flirt with ideas of culture and lifestyle, but it is the deviation in character that is particularly telling. Both versions deal with a broken family at the nucleus of a haunted house story. Mama bear love and paternal guilt tug at the parents in both movies; however it is the characterization of the father figure that reflects a glimpse of cross cultural ideals and expectations.

Ryuji, the father in the original, starkly contrasts his fictional American counterpart, Noah (Martin Henderson). Noah is a rogue photographer whose streak for individualism embodies an American prototype and leaves him too charmingly arrogant to wear the traditional necktie of fatherhood. Ryuji is a workaholic, and his stiff commitment to his academics sculpts a Japanese cliché and shines a light on struggle for Japanese parenthood. And in both versions, these paternal figures are killed-off for their failures. Or perhaps, they were simply in the way of a good horror movie kill.

Final sequence of The Ring. Martin Henderson doesn’t exactly die with his boots on.

And since we’re at the ending, let’s talk about it: Verbinski’s version broke the American mold of horror in part to remaining faithful to Ringu‘s ending. Normally, American horror ends its stories by extinguishing the source of horror completely. See King Kong (1933), The Blob (1958), and The Excorcist (1973) for examples. In short, the monster dies in America, but Japanese horror endings linger like atomic fallout.

Nakata serves up a healthy dose of anti-resolve in a final plot thread that leaves daddy dead and mommy with the discovery that the cursed tape allows its viewer to live if-and-only-if they copy the tape and copy the curse. It’s a story hook that kindles fear, fuels franchise investments, and speaks sequels for Hollywood’s love affair with foreign horror re-makes.

Takeshi Miike echoed the Ringu to similar results with Chakushin Ari (2003). Similar to Ringu, Miike’s movie deals with fear of death and perhaps a fear of technology. Here are the particulars: people begin to hear voice messages from themselves as they are dying. Sound like Ringu? Its results were similar as well, and if you’re thinking it sounds like that Ed Burns movie you caught on T.V. the other night, you’d be right. Hollywood translated Chakushin Ari into One Missed Call in 2008.

Takeshi Miike echoed the Ringu to similar results with Chakushin Ari (2003). Similar to Ringu, Miike’s movie deals with fear of death and perhaps a fear of technology. Here are the particulars: people begin to hear voice messages from themselves as they are dying. Sound like Ringu? Its results were similar as well, and if you’re thinking it sounds like that Ed Burns movie you caught on T.V. the other night, you’d be right. Hollywood translated Chakushin Ari into One Missed Call in 2008.

Many other re-makes could be mentioned, but some of the most notable titles include Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish vampire flick, Let the Right One In (2008) which was reborn into Let Me In (2010) under the direction of J.J. Abrams collaborator, Matt Reeves. Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-on (2002) cannot be ignored; also hailing from Japan, the remorseless ghost story paved way for a second Japanese film, Ju-on: The Grudge (2003) and was shadowed by two more American Grudges, the second in 2006 and the third in 2009.

Similarly, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo franchise was a smash hit before and after Hollywood snatched up the story. After the original Swedish film by Niels Arden Oplev enthralled movie-goers in 2009, Hollywood A-list director, David Fincher, captured the story within his frame. Spike Lee too looked abroad in 2013 and converted Chan-wook Park’s nightmare-fueled tragedy, Old Boy (2003), for American viewers. A noble effort in a corrupt cause, perhaps, but another example of the overseas inspired trend.

From a financial angle, it’s no surprise that Hollywood investors would piggyback their way to the bank with an entertainment package that had proven its worth in the international arena. Existing properties are proven markets. Let’s consider the case of the film geek that saw Ringu and is soured at the news of the Hollywood re-make. Guess what? He’s going to buy a ticket because geeks might rant and rave about minutia, but at the end of the day they’re dollar signs to Hollywood investors.

It’s just good business, and horror isn’t a lone wolf when it comes to the remake game. The Korean crime thriller, Infernal Affairs (2002), became The Departed (2006), which earned Martin Scorsese an overdue Oscar win for best director. You can add the Al Pacino/Robin Williams thriller, Insomnia (2002) to the list. Based on the Norwegian film of the same title, its narrative orbits around the murder investigation of a local teen. And before that, you have the highly undervalued and under-seen Kurt Russell creeper, The Vanishing (1993), began as the Dutch language film, Spoorloos (1988), just five years prior—and the index rolls on: True Lies (1994), The Talented Mr. Riply (1999), Vanilla Sky (2001) , Passion (2012), and Ghost in the Shell (2017) are a few American titles that all owe their existence to foreign studios and audiences.

It’s just good business, and horror isn’t a lone wolf when it comes to the remake game. The Korean crime thriller, Infernal Affairs (2002), became The Departed (2006), which earned Martin Scorsese an overdue Oscar win for best director. You can add the Al Pacino/Robin Williams thriller, Insomnia (2002) to the list. Based on the Norwegian film of the same title, its narrative orbits around the murder investigation of a local teen. And before that, you have the highly undervalued and under-seen Kurt Russell creeper, The Vanishing (1993), began as the Dutch language film, Spoorloos (1988), just five years prior—and the index rolls on: True Lies (1994), The Talented Mr. Riply (1999), Vanilla Sky (2001) , Passion (2012), and Ghost in the Shell (2017) are a few American titles that all owe their existence to foreign studios and audiences.

Undoubtedly the prospect of an English language re-make is a tempting fruit; one that Michael Haneke is no stranger to. By his own volition, the celebrated filmmaker undertook the task to translate his very own Austrian film, Funny Games (2017). Katey Rich incorporates her unique vantage point on the re-make in her interview with Haneke at CinemaBlend.com:

[He] has chosen to remake his 1997 film, Funny Games, shot-by-shot; the only difference is the actors, all English-speaking, and the location, which is pretty much exactly the same as the first one. The concept, of course, is identical: A rich family in their vacation home is taken hostage by two young men, who embark on a series of “games” with the family that all end in torture, humiliation, and death. But this isn’t the “torture porn” you’re used to, oh no. The moment one of the killers looks into the camera and winks, you know you’re in new, highly experimental territory.

When Rich asks Haneke directly about the remake, his response indicates precision in translation. He explains, “I didn’t have to add anything, and just to change it a little bit I thought was dishonorable. If at all, it became almost a gamble with myself, whether I was able to do the exact same film under very different circumstances.”

So translation and shared stories makes sense artistically and financially; in the case of the Ringu movies and so many foreign horror remakes, we see that fear is familiar and screams are part of a universal language, but beyond the politeness of cross cultural business banded by money and within our American gates, horror movies are addressing the country’s differences.

When nightmares resonate in mass appeal (read: ticket sales), the bad dream might be more telling than meets the eye. Flip back the calendar half a century, and you’ll discover George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead to be one of the most confrontational horror films of the year—a story that parallels the claustrophobic paranoia of a 1968 America that was turning in on itself amidst its incendiary struggle for Civil Rights and equality in sex and nomenclature. Gutsy and subtle in the same stroke, its release follows the assassinations of RFK and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Romero’s shoe-string landmark shocked audiences with imagery that presents: 1) an unusual brand of slow moving, eternally gluttonous zombies; and 2) an black hero who, after surviving a mob of ghouls, is thoughtlessly shot between the eyes by redneck law. As grim as an ending could be, Romero puts his audience through the ringer, and after all the blood, sweat, and more blood, he tells us in 1968 that it’s not going to be okay. At least not for a while.

And if Romero was telling us the brawl for racial equality won’t be an easy fight, contemporary horror movies are echoing his call and telling society that it’s still not okay. And he was right—racial tension in America is higher than has been in recent memory, and all the while modern monster movies are getting in your face about it, just as society as is getting in each other’s face about it.

And maybe that’s progress. Just like a spat in your personal life, sometimes problems are addressed with whispers before shouts, and it’s not until the fight reaches its zenith that tensions can begin to resolve. So maybe shouting is better than politely holding tongues. Horror movies might be suggesting the same, and the genre is shifting its reaction to the struggle of inequality from soft spoken subtlety—as in Night of the Living Dead’s zombie metaphor—to a roar, most popularly exemplified by Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). The surprise hit is a socially conscious film that sold the hell out of some popcorn and wears its heart on its sleeve. The horror mystery tells the story of an affluent white community who kidnaps black men to snatch their bodies and transplant their aging consciousness into young, able bodies, a premise is as imaginative as it is unapologetic.

And maybe that’s progress. Just like a spat in your personal life, sometimes problems are addressed with whispers before shouts, and it’s not until the fight reaches its zenith that tensions can begin to resolve. So maybe shouting is better than politely holding tongues. Horror movies might be suggesting the same, and the genre is shifting its reaction to the struggle of inequality from soft spoken subtlety—as in Night of the Living Dead’s zombie metaphor—to a roar, most popularly exemplified by Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). The surprise hit is a socially conscious film that sold the hell out of some popcorn and wears its heart on its sleeve. The horror mystery tells the story of an affluent white community who kidnaps black men to snatch their bodies and transplant their aging consciousness into young, able bodies, a premise is as imaginative as it is unapologetic.

Before Get Out, the terror thriller, Green Room (2015) set America’s racist underbelly as a source of horror in a plot that captures a young and carefree punk band, in a neo-Nazi venue where they witness a murder that makes them a liability. The Purge: Election Year suggested the danger of class-system animosity in a national holiday of bloodthirsty catharsis to design the story’s foundation. In her article for vox.com, Aja Romano tells us that “the home-invasion trope has been part of cinema since cinema has existed… [and] metaphorically, the allegory of the modern home invasion film is all about the sanctity and deceptive sovereignty of America as a nation state, powerful and impenetrable.” This of course smacks of fears rooted in post 9/11 terrorism and immigration—and cinema’s reaction is to punch the proverbial bull shark in the nose.

Before Get Out, the terror thriller, Green Room (2015) set America’s racist underbelly as a source of horror in a plot that captures a young and carefree punk band, in a neo-Nazi venue where they witness a murder that makes them a liability. The Purge: Election Year suggested the danger of class-system animosity in a national holiday of bloodthirsty catharsis to design the story’s foundation. In her article for vox.com, Aja Romano tells us that “the home-invasion trope has been part of cinema since cinema has existed… [and] metaphorically, the allegory of the modern home invasion film is all about the sanctity and deceptive sovereignty of America as a nation state, powerful and impenetrable.” This of course smacks of fears rooted in post 9/11 terrorism and immigration—and cinema’s reaction is to punch the proverbial bull shark in the nose.

In addition to race, horror continues to address equality among gender. As Beth Younger points out in her article for Quartz.com, movies have men speaking twice as much as women with exception of one genre: you guessed it, horror. Seeing women in danger is certainly a fetish that male horror filmmakers have brought to the social consciousness (for examples see just about every Hitchcock film ever made and the multitudes of films that were inspired by them), and so it is no surprise that ladies often lead these stories, but does this tell us more about our fears or our desires?

In addition to race, horror continues to address equality among gender. As Beth Younger points out in her article for Quartz.com, movies have men speaking twice as much as women with exception of one genre: you guessed it, horror. Seeing women in danger is certainly a fetish that male horror filmmakers have brought to the social consciousness (for examples see just about every Hitchcock film ever made and the multitudes of films that were inspired by them), and so it is no surprise that ladies often lead these stories, but does this tell us more about our fears or our desires?

Younger asserts that “the genre has moved from taking pleasure in victimizing women to focusing on women as survivors and protagonists” and lists titles such as Jennifer’s Body (2009), The Conjuring (2013), and The Witch (2015) as cases of point.

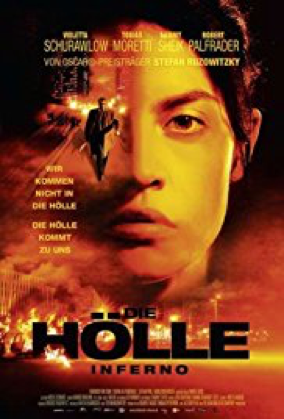

One of the great opportunities of foreign-film remakes is the ability to juxtapose. Is America’s progress part of the progress of the world, or is the country on its own timeline? Looking at 2017 alone, several titles are making waves for female representation—Die Holle (Cold Hell), an Austrian film that exposes the horrors of a woman cab driver, who must stand up to sexual aggression. She eventually embarks upon a search for a serial killer who targets female sex workers of the Muslim faith. Another title, Revenge, shares a similar theme. Our leading lady’s rape serves as the catalyst for this revenge movie that promises as much survival as vengeance. South of the border, Tigers Are Not Afraid serves as another germane example. The Mexican suspense flick trails a young girl with strange visions who survives her mother’s murder and navigates a slum surrounded by sex trafficking, dope zombies, political corruption, and gang violence. The twisted fairy tale is written and directed by Issa Lopez and is brimming with depth and imagination.

One of the great opportunities of foreign-film remakes is the ability to juxtapose. Is America’s progress part of the progress of the world, or is the country on its own timeline? Looking at 2017 alone, several titles are making waves for female representation—Die Holle (Cold Hell), an Austrian film that exposes the horrors of a woman cab driver, who must stand up to sexual aggression. She eventually embarks upon a search for a serial killer who targets female sex workers of the Muslim faith. Another title, Revenge, shares a similar theme. Our leading lady’s rape serves as the catalyst for this revenge movie that promises as much survival as vengeance. South of the border, Tigers Are Not Afraid serves as another germane example. The Mexican suspense flick trails a young girl with strange visions who survives her mother’s murder and navigates a slum surrounded by sex trafficking, dope zombies, political corruption, and gang violence. The twisted fairy tale is written and directed by Issa Lopez and is brimming with depth and imagination.

Looking back at Ringu—we can see the film chips away at patriarchy. The Japanese adaptation of the novel makes a significant revolution. It moves the protagonist from a married male to a divorced, single mother, which allows the conversation of female representation to develop. The American remake does the same, providing audiences with a heroine that on one hand takes charge of her career, but on the other hand, cannot be excused from her maternal duties. It’s a realignment of female identity in the horror tradition, but Verbinski’s American stab takes a step backwards. The Ring shows Rachel to maintain a resentment of motherhood, a conservative oversimplification of the work-family tight-rope that a single mother must balance. In her introduction scene, she’s both vulgar and glib to her son’s needs. As the story continues to build, Rachel’s parental flaws and her ex-husbands role in the film and family suggest the need for a paternal presence.

While the American film remains more conservative than its Japanese predecessor, both versions play into an genre evolution that presents women as survivors rather than objects of sex and violence. There’s no doubt that the movie world is offering opportunities for female perspectives throughout culture, but with new seasons of cinema upon us, the question of whether the world wants to hear these stories will soon be answered.

As for the dollars—they might tell you more about marketing packets than they do about the movies, but the movies themselves? They tell us everything. They tell us about our hopes, dreams, and nightmares. They shows us at our most primal and at our most civil. At our strongest, and at our weakest. They show us how we hate, and they show us how we love, and most importantly, they shows us how we do both.

The inescapable truth is that cinema’s influence on itself remains somewhere between chronic and incestuous, but with such a rich history of tossing stories back and forth across the proverbial pond, it’s safe to say that humanity has found more in common with each other than just ticket sales. So in an era of Hollywood that is plagued with sexual predators, cultural misrepresentation, and embarrassingly unequal pay and opportunity for women, there is still some slashing to do get to the root of the American disease.