Either you clicked on this article because you took the title’s bait or you genuinely seek to learn some film theory. My goal in doing this is not to bore you, but to hopefully have you retain something in comparing theories to Lindsay. Let’s dive into this: there are many mediums of art that try to capture life, varying expressions or some kind of phenomena, typically through the work of one artist. Film, however, challenges these philosophies in that it is a medium of art that arguably attempts to do the same thing, but due to its technological nature, and its production process, sometimes falls short when compared to the qualities we find in other forms of art. Film theorists have tried to simplify (or, complicate?) the true nature of cinema and where it lies in terms of its other artistic counterparts.

Walter Benjamin was a theorist whose ideas were based on film and its relation to the screen, Christian Metz focused on individual spectators, and Ann Kaplan theorized about society and how it reflects the films we watch. We will explore their theories and elaborate on which of these three theorists offers the best road map for understanding film and its impact in our world. In doing so, I will endeavor to make these topics less dense and compare theory with popular culture (we love you LiLo).

Walter Benjamin

Walter Benjamin (pronounced ‘ben-na-meen’) was a theorist with interests that focused on the ‘reproducibility’ of film, the representation of human beings on screen, and how these ideas demonstrated the ever-changing human perspective. Benjamin makes a convincing claim in that his theories ask the question of, why film can be like any other form of art if the core of its existence relies on it being reproduced. He uses the screen as a way to theorize his beliefs on the essence of cinema and how it derives from formal conventions and technologies. Where pieces of art like the Mona Lisa – if reproduced – would lose their prestige compared to film as an art form. Benjamin writes in regards to these forms of art, “It is this unique existence – and nothing else – that bears the mark of the history to which the work has been subject.” What he is saying here is that the whole sphere of authenticity eludes technology, not only that, but technological reproduction strips away the aura that exists within traditional art. Yes, Benjamin would really hate snapchat. Benjamin believes that stripping away this aura and producing massive amounts of art creates a sense of sameness in the world, extracting what is unique while taking away an appreciation of its historical context (let that sink in…)

Benjamin goes on to discuss the role of actors and their relationship on screen through their connection with technological apparatuses – he points out that actors on screen are aware of these apparatuses, and the fact that they are recording what will be displayed for the masses. This puts actors in vulnerable position as Benjamin writes, “It is they [the audience] who will control him [the actor].”

To Benjamin’s point, Lindsay Lohan finds/found herself in an almost parallel position to that of the actors that he describes. The paparazzi’s addiction to publicizing her life in the early 2000’s (and your unwavering desire to follow her life) put Lohan in a position where she’s aware of the fact that these photos will be shown to vast amounts of people, which put her in a vulnerable situation – yet she continued to behave in ways that drew what seemed to be undesired attention on her part.

Christian Metz

Metz takes a rather psychoanalytic approach as to why people enjoy going to the cinemas and seems to ask, what is it about the cinema that is so intriguing and why do so many people devote their time and money to watch a film? (It’s a valid question!) He focuses on the individual spectators and what their physical and psychic structures bring to the films they watch. First, Metz believes that we go to the cinema to participate in a voyeuristic gaze and to fulfill this desire of being able to look without being looked at. Metz believes that a component to all films is the subjectivity the audience derives from decoding the meaning of the film. Throughout our time in the cinema, we identify with the camera as it fulfills our desire of allowing us to look into a life unlike our own. If we did not attempt to identify with the film, Metz writes, “…film would become incomprehensible, considerably more incomprehensible than the most incomprehensible films…”

This too, is similar in what we see with people’s desire in publicizing the life of Lindsay Lohan (and Kanye and Miley and Biebz and Zuckerberg). The tabloids have made it simple for us to look into the life of a celebrity never having to experience any kind of consequence. Like the actors on screen, Lohan fulfills this desire of providing people with this sense of; ‘I’m glad that’s not me, but god this is gold’ mentality – or “schadenfreude.” This leads to the next question of why we enjoy peeping into the lives of these non/fictional characters. Metz believes that when we go to the cinema we are given this false perception of reality. Metz links this phenomenon to the idea of the mirror stage, a concept of Lacan, and challenges this in saying that films work less like a mirror and more like glass. He challenges Lacan’s theory because he believes that spectators have already experienced the mirror phase in their personal lives, so they are able to constitute and relate to everything that is already within the film. Thus, he rejects the notion of the mirror stage within films because he believes that the only things not reflected in films are the spectator’s bodies themselves, consequently becoming a clear glass rather than a mirror.

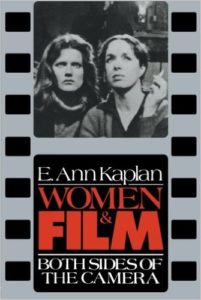

Ann Kaplan

Ann Kaplan, like Metz, was interested in the psyche and nature of the spectator believing that Hollywood acted as a portal to our “patriarchal unconscious”, which could be decoded through psychoanalysis. However, Kaplan was concerned with the intended gaze that films put on their audience and challenged many feminist film theorists’ ideas of the masculine gaze, including what this said about society. Unlike Benjamin and Metz, Kaplan was concerned with the social forces that help shape the collective medium of film. Most feminist film theorists pointed the finger at Hollywood and how many narrative films since their inception were highly masculinized – producing films with predominant male gaze while objectifying women and using them largely for sex appeal. Kaplan, although she agreed with this notion, challenged the definition of the male gaze. She believed that although a male gaze exists in almost all films, it is rather a question of dominance versus submissiveness, and any actor, be it male or female, can participate in these roles. She writes, “we need to analyze how it is that certain things turn us on, how sexuality has been constructed in patriarchy to produce pleasure in the dominance-submission forms, before we advocate these modes.”

She uses John Travolta as an example in that in many of his early films he, as she points out, played a submissive role (Urban Cowboy anyone?). This put female spectators in the dominant position allowing them to participate in this supposed masculine gaze. She points out that just because the gaze is masculine doesn’t mean it’s meant for men, but instead there will always be a gendered gaze inverting this innate hierarchy. In the case of our girl Lindsay, Kaplan would undoubtedly argue that she is objectified through tabloids and other sources of mass media. Lohan, like the idea of male dominance, is a construction of western society and the pressure put on celebrities might explain her irresponsible lifestyle. Lohan, to Kaplan, is neither a victim of male or female gaze but instead a victim of societal gaze as it seems that she is being used as an example of the negative impacts of, in her case, being a celebrity… and we see it time and time again, sadly/ironically to very people who work to entertain us.

Although each of these theorists offers an insight into film, Walter Benjamin is the theorist that in my opinion offers the best road map to understanding film and its relation to the world (big ‘effing statement, I know); but I chose his theory because of Benjamin’s explanations of the actor and the ‘reproducibility’ of film, which is on par to Lohan’s situation. Benjamin is the only theorist to point out the noticeable amount of pressure an actor endures while subjecting themselves on screen for the masses, knowing that it could potentially cause criticism that could make or break their career. Benjamin would argue that the reproduction of these largely negative tabloids have without a doubt caused Lohan’s (and seriously every other living actor) personal life to be put onto display and for her overall credibility, or arguably her aura as he might say, to be challenged as an actress going forward. I think many of us would agree, Mean Girls was sort of the last of Lohan’s best.

In the end, Benjamin, Metz, and Kaplan are theorists that share a passion for film but take a different approach on their insights to the overall essence of cinema. With the help of Lindsay Lohan, I hoped to have demonstrated only a portion of these theories via the intricacies of our pop culture.