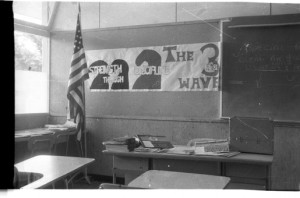

Classroom at Cubberley High School sporting a “3rd Wave” poster

I learned about the existence of Die Welle one morning in high school as I casually looked over the 2008 Sundance Film Festival catalogue, only slightly bitter that my TV Production class would be attending while I stayed home. My first thought was bemusement that German filmmakers decided to set a little-known social experiment conducted at a Bay Area high school in 1967 called “The Third Wave” in contemporary Berlin. Essentially, the Third Wave was the brainchild of young, Stanford-educated history teacher Ron Jones, whereby turning his classroom into a proxy totalitarian regime with himself as leader he hoped to unpack what autocratic government meant. A deviation from the traditional lesson plan to be sure, it ended with hundreds of students prepared to create a radical third political party, and himself kicked out of high school forever.

My next thought was that I should tell my father, Phil, about this. He was in the midst of producing a documentary on the experiment from the point of view of the students involved, of which he was one.

Fast-forward a few months and I’m filming b-roll of snow out the window of my dad’s rental car as we make our way to Park City, Utah for the premiere of Die Welle. After I showed him the catalogue he decided that meeting director Dennis Gansel and his crew would be beneficial to explaining just how far abroad this story had spread. For grade-school students in Germany, as well as a number of schools in the U.S. and Israel, the The Wave novelization by Todd Strasser is required reading. The novel itself is adapted from a 1981 TV special, which is in turn adapted from Ron Jones’ original short story. During an interview in Phil’s film (at this point titled Lesson Plan), Dennis admits that this book is a common bond for German teenagers.

“Die Welle” director Dennis Gansel at the Sundance Film Festival in 2008

Please consider, then, the fact that Phil and Dennis both were students of the Third Wave who made feature films on the subject in opposing styles. Maybe it is just personal taste that one man made a documentary while the other chose fiction, but these decisions are also important for discussing the filmmaker as a self-reflexive storyteller.

Let us start with the obvious, the fact that the filmmakers come from different generations and countries. The Baby Boomers are arguably the most well-documented generation to have ever lived, yet Israeli schoolchildren know more about The Wave than the average American. There is a profound lack of websites, investigative biographies, and History Channel specials. Phil reasoned that a play-by-play narrative told firsthand by some of the main actors would be welcomed by his generation as a unique retrospective that offers nuance to a time largely defined by hippies, protest, and civil rights. After all, if Tom Brokaw could still sell books and TV shows on such well-trod history as the year 1968, why wouldn’t the 60s version of “The Hunger Games” find a home?

The Wave may have connected Phil to a couple hundred of his classmates, but it connects Dennis to his entire country. Perhaps similarly to how the “traveling gunfighter” motif links U.S. and Japanese popular history vis-à-vis the wandering samurai, a leader ordering his people to their doom contains special cultural capital in Germany. In a 2011 interview with MovieWeb.com, Gansel is asked if he considered setting his film in America, to which he responds “No, not at all…I asked myself, ‘What about my generation…Could this happen again?” Ironically but understandably, fictionalizing The Wave created a box-office hit in Germany precisely because it answered that question, What about us? The ability to bring a story home is one of the beauties of fiction, and for evidence just look at the Golden Age of Disney animation.

Many documentaries, conversely, find success in the idea that you can turn the familiar into the unfamiliar. 3 of the top-grossing docs in 2008, Religulous, Man On Wire, and Up the Yangtze turn pedestrian settings and subject matter (religion, New York City, and China’s largest river, respectively) into dreamscapes and nightmares. Die Welle presents the horror of the situation to be sure, but there is unease hearing members of the generation that gave us Steve Jobs, Meryl Streep, and Bill Clinton likening their childhood friends to the Gestapo that cannot be reproduced (well, maybe Meryl makes sense).

Lesson Plan also seeks a resolution between characters, or at least the beginnings of a dialogue. In a scene only possible in documentary, we see this dialogue take place between Jones and a handful of his former students in the original room where the experiment ended. I can attest that even after the film’s ending the discussion of what was learned by The Wave and what should have happened to Ron Jones continued; among other screenings, I was present at Q&A sessions at the Mill Valley Film Festival and at Gunn High School in Palo Alto, CA.

In Die Welle, on the other hand, we see a resolution that is highly dramatized but also sadly reflective of the current reality; school shootings and other explosions of public violence are no longer anomalies. Both films call for vigilance to the abuses of authority, but Die Welle seamlessly updates this to include the lonely and disenfranchised edges of society we happily ignore until it is too late. The film is very much of its time by showing a desperate young man kill for the ideology that gave him meaning.

I believe both sets of filmmakers employed their narrative medium because it matched how the story played out in their minds. They told it the way they tell it to themselves, and found success in honesty. Lesson Plan will live on indefinitely, as a teaching aide in classrooms and as historical television, enlightening youth with the experiment sans the fallout. Die Velle made a splash at Sundance and in Europe, exposing the story to a large immediate audience while also allowing Dennis to grow as a filmmaker. The forces that brought both to production are complementary such that it is difficult to imagine one film existing without the drive that created the other. Die Velle obviously would never have been made without the kind of fact-finding that led to its predecessors, and Lesson Plan found traction thanks to the imaginations of complete strangers who also learned from The Wave.