There are many ways to look at films, and to have conversations about what we as filmmakers do and ought to do. The conversation is usually centered around artistry, business and entertainment – but only rarely is film discussed as an inherent good for society.

Film is Art. Film is Commerce. Film is Entertainment. Film is Storytelling. Film is Media. Film is Technology. Film is History. And – that is my proposition – Film is a Service to the Public.

Film as Art

Film has lots of aspects – and it is each and every aspect that makes it such a unique form of expression. When we think about Film as Art, we might think about the Arthouse realm, the experimental and Avant-Garde films, the films that push the envelope. Many of us independent filmmakers want to create art or self-identify as artists. We are the creative people, the ones with crazy ideas that provoke and inspire, the ones that are not afraid to express their feelings through the media they create. Films are created by artists – oftentimes dozens or hundreds of artists in various disciplines and with varying skillsets that compliment each other in the collaborative environment that filmmaking provides. And deep down, nearly every filmmaker hopes to create something that will be seen as a work of art.

Film as Commerce

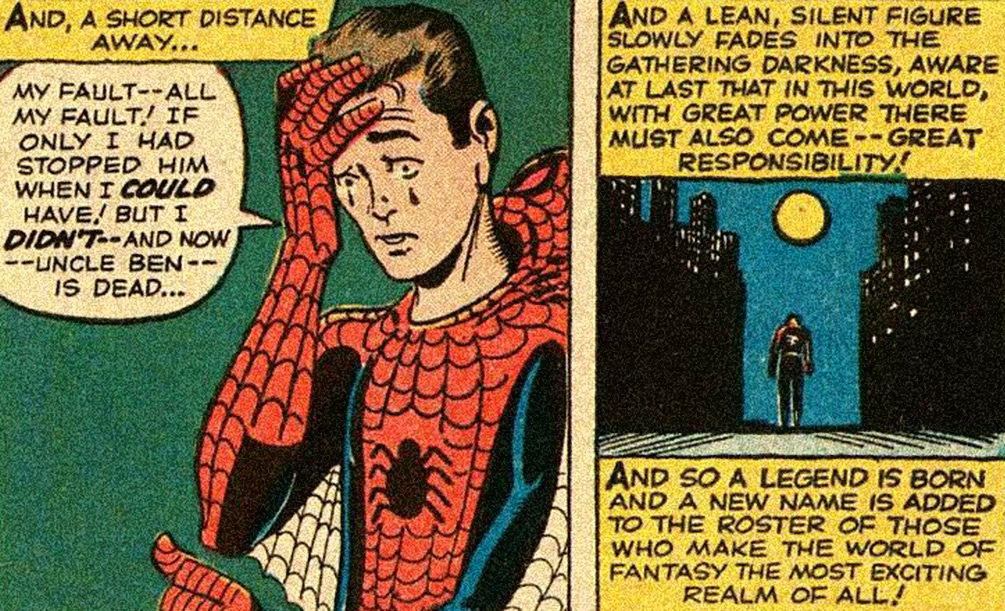

Great power necessarily implies great responsibility

Closely tied to art – and oftentimes mistakenly seen as its polar opposite – is the commercial aspect of filmmaking. Films are expensive to make; they employ large numbers of specialized, experienced people, they incur a great deal of rental expenses in equipment, design materials and locations, and they take many months to complete. For that matter, films are subject to investment and financing; someone needs to take a relatively high financial risk in putting together the budget for said film. The investment aspect goes hand in hand with a profit motive, which in turn motivates a lot of decision making: The more a film costs, the more it needs to be clear, accessible, entertaining, and spectacular … oftentimes sacrificing creative wishes from the makers in order to allow a success at the box office and raise the filmmaker’s chances of being financed for their next film. Not seldomly these budgets are in the millions – an extraordinary sum for something as unpredictable as a story being told.

-Lord Melbourne, 1817

Film as Storytelling

When we watch narrative films, our deep desire of telling stories and hearing stories is being fulfilled. We are able to experience life vicariously through the eyes of someone else; externalize our internal moral codex and re-evaluate our emotions based on the stories we hear and see. Films communicate stories in a multidimensional way, transcending the parallel storytelling abilities of just about every other medium by far. Films can tell stories that books and theater plays can only deliver in far greater time spans: Film compresses visual and auditive information about characters, surroundings, time spans and relationships in a tightly packed multi-level narrative that entertains us.

Film as Entertainment

When we consider what film initially replaced – the Vaudeville theater, the lowbrow entertainment choice of the population – it becomes apparent that film still has a dominant role in the modern entertainment world. We sometimes want to numb ourselves from our personal lives and just be taken away in a strong narrative, become one with the silverscreen. We like to laugh and be entertained, and keep exploring possibilities on spending our free time as much as possible with entertainment of various media.

Film as Media

By being able to deliver information in analog and digital forms, both on an auditive and visual level, film is a medium with high information density and a heritage of other media forms, such as the theater, the novel and the realm of photography. Film is a communication device that can be delivered through various media outlets; in our modern world we can choose between cinema, TV, online services on Computers and soon interactive VR experiences as our means of receiving films. These technologies are indicative of the place that film has in our society.

Film as Technology

Being able to process motion out of 24 single images per second is part of why cinema works in humans. Capturing light on photosensitive emulsions or electronic image sensors allows for a reproduction of the moving image. Cinema was, first and foremost in its initial stages, a series of technological breakthroughs and developments: Muybridge’s capturing of discrete motion on media; Edison’s streamlined camera system, the Lumiere’s camera-projection hybrid that gave name to the field of Cinematography: We’ve seen film develop technologically from the humble beginnings in the 1890s all the way to an incredible diversity of ever-advanced capturing and reproduction formats in analog and digital realms.

Film as History

More than 120 years have passed since the inception of cinema technology, and in that vast time span, human history has seen two world wars and technological shifts of a massive scale – all of which was recorded on film. Film has a history of its own. Film has historical movements and streams, schools of thought and approach. Film interacts with other historical art movements and we can learn quite a lot about an era by watching films made during that time. We can study the historical succession of various master filmmakers and how each of them influenced one another. Film depicts and reproduces our political and social history.

The above approaches to filmmaking and film consumption are only a selection of possible viewpoints, but give a good overview of how we perceive film production as a field of interest and as an occupation.

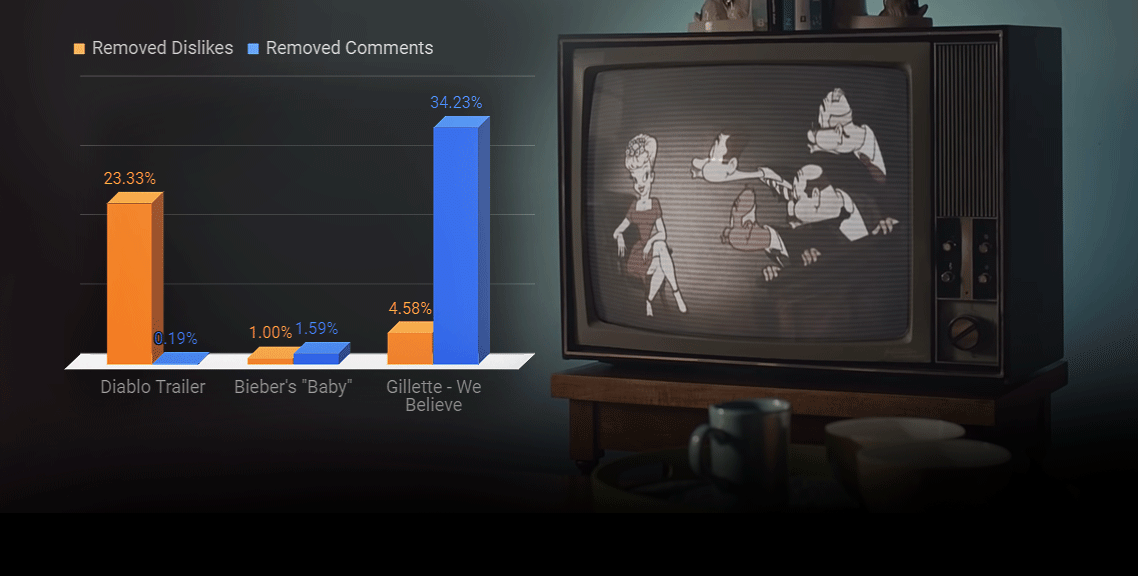

What none of these perspectives pays enough attention to – and that is the case “out in the field” as well as in film school – is the power that film has on society. Films have triggered social change – like the outburst of racism after “Birth of a Nation” or the questioning and eventual dismantling of the Super-Size fast food as a result of the popular documentary “Super Size Me”. This is the area that we are most interested in, and that’s why we created a magazine to have a platform for exploring this incredible potential in film. Films that are made for mass audiences – anything north of a budget of a few hundred thousand dollars could easily be considered “mass media” – can have an impact on its audience. The filmmaker and producers become communicators to a huge amount of people, regardless of their training in politics or sociology.

That’s why I suggest a shift in perception and self-image: A filmmaker should not just think of themselves as an entertainer or artist, but first and foremost as a benefactor to the audience: The filmmaker as a public servant.

Film as a Service to the Public

Just for the mere fact that we create films for a big number of people, we need to be conscious of what we are doing: How much of our own bias we are including in our film. How many assumptions are we making about life when creating stories? How paternalistic are we when telling other people’s real stories of hope and suffering, and how much of their story do we actually understand?

How influenced are we as filmmakers by the ideology that we have been indoctrinated with by the society we grew up in, and to what extent are we reproducing that ideology? We have to take a step back and look at oursevles: Who are we? Why are we making films? What is the ultimate goal here?

We as media makers have immense power over the people that consume our media, and nearly 100 years of research in the fields of sociology, psychology, media studies and film studies confirms this assessment. It is important to not just be aware of that power, but also to use it with responsibility.

We can therefore say: With a powerful global film industry comes a global responsibility. This responsibility is to be taken seriously not just by the filmmakers that create the films, but also by the studios that develop these films, by the writers that take on the responsibility of dreaming up stories that are infused with ideologies, by the production companies that make films a reality, and by the distributors that empower film impact through a global distribution model.

Redefining the Identity of the Filmmaker as a Public Servant

As filmmakers, we have certain shared identities that come with the profession. Each filmmaker has their unique priorities and values, so the composition and prioritization of these identities varies greatly. The possibly most prevalent identifiers for filmmakers are as artists or as storytellers, the much-desired label of the “auteur”. What we have seen throughout this paper is that film is impactful; film can change people and can change the world in ever so small increments. That’s why I think it is important to redefine, repurpose, restructure the idea that we have of the prototypical filmmaker: Not someone who goes and creates art for their own liking, gets respect for their personal wealth and power, who walks the red carpet of festivals to go to bed feeling accomplished and admired.

The prototypical filmmaker in our minds should be a person that gets up in the morning to serve the public. We have grown cynical of the term “public servant” because we associate corruption, bureaucracy and self-serving interests with it; the “public servant” in our minds is often synonymous with politicians that deviate from the ideal.

Nevertheless, it is the most accurate description for what a filmmaker should be doing: Creating useful and powerful media that allows its audiences to be reflective, critically thinking individuals.